The MAHA Report: Doing Our Own Research

Part III of Reading the MAHA Report so You Don't Have to

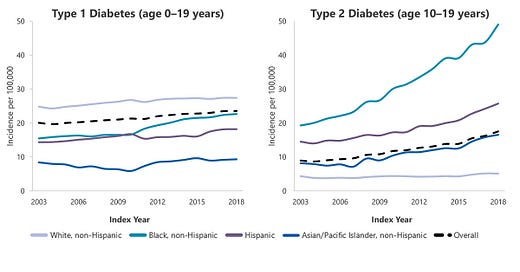

RECAP: On Feb 13 2025, President Trump issued an Executive Order to create the Make America Healthy Again Commission, and directed them report on the “childhood chronic disease crisis”. The Commissio…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to E is for Epi to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.